Author: Eve Andrews

This story is part of Grist’s Summer Dreams arts and culture series, a weeklong exploration of how popular fiction can influence our environmental reality.

People thought the snake spotted in the park was a black mamba. Who knows how a reptile that normally makes its home in sub-Saharan Africa could have slithered its way over to the East End of Pittsburgh — or why it would want to make that particular trek — but there it was, wrapped around a beech tree in the middle of Frick Park back in April.

Of course, everyone in the neighborhood lost their minds. A highly venomous snake right there where people go jogging and walk their blissfully unsuspecting labradors and terriers? Call the police if you see this thing, people posted on Facebook, and sure enough, somebody did. One local news station sent a chopper. (“It’s no garden snake — look at this thing!” said an incredulous anchor.) The department of public safety issued a citywide alert.

But the people more familiar with the ecosystem, those who knew their non-human neighbors, were aghast. The police? For what? That thing was a ratsnake. A big one, but sometimes they get that big — six, seven, even eight feet long! Native to the eastern United States, a resident of Appalachia since long before the first Indigenous people ever set foot on the land, before the first stone of Fort Pitt was ever erected or the first rock of coal ever pulled from the ground. Not venomous, not dangerous, and certainly not out of place.

“These are very docile, fragile animals,” explained Chris Urban, chief of natural diversity at the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. “I’m hoping someone on the police force was aware of what it was, that it wasn’t dangerous and such. I don’t even know what the fate of the snake was, but I tried to quell those fears quickly, that it was just an eastern ratsnake and wasn’t a harmful animal.”

A naturalist who lived on the border of the park actually recognized the individual snake in the police-baiting Facebook post, according to Stephen Durbin, a biologist with Pittsburgh’s Frick Environmental Center. “Pete said to me, ‘I’ve seen that snake in that tree many times over the years, and it would be a shame if something were to happen to that snake because somebody thought it was where it shouldn’t be, that it didn’t belong in its home,’” Durbin said.

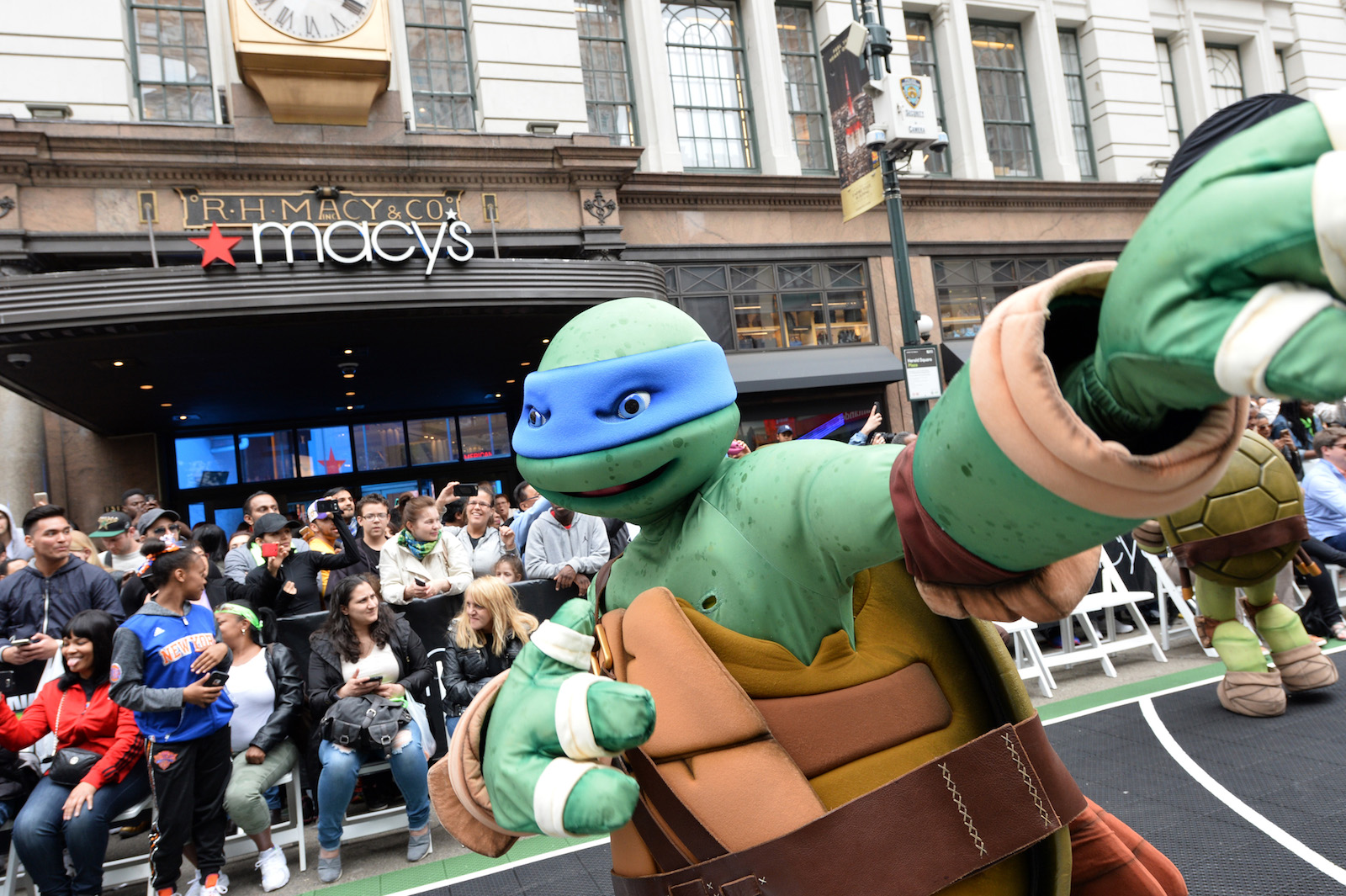

City children grow up with the idea of urban reptiles being freakish, in some way or another. My particular generation, for example, had the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, a band of turtles morphed by a “mutagen,” an alien substance, and all their monstrous friends and enemies: Mondo Gecko, a skateboarding lizard; the Punk Frogs, which are exactly what they sound like; and Leatherhead, the sewer alligator, who is most interesting to me.

He’s a real tragic figure, Leatherhead, misunderstood by humans and turtles alike. Escaped from a pet shop, and then transformed by aliens to a hulking, hyper-resilient mutant with an uncontrollable rage problem. When an accident separates him from the aliens — whom he considers his family — he retreats to the safety of the sewer. There’s no rest for the weary Leatherhead, however, because he’s pursued by a big-game hunter eager for his hide. That’s how he eventually joins forces with the turtles, who show him how to make a quiet, safe home down in the sewer, which is all that he wanted all along.

The legend of alligators in the sewers of northern cities is roughly a century old. One plausible origin story is that urbanites in the early 1900s ordered baby alligators by mail or brought them back as souvenirs from trips to Florida and the Gulf region, and then flushed them or set them loose when they started to grow out of a manageable, diminutive size. Very few alligators have actually been found in sewer systems or local watersheds over the years, but the strength of the imagery kept the story alive. One example in New York’s Westchester County in 1932, as described by Gizmodo, involved children running to the police to let them know that the local river was teeming with crocodiles. “The body they brought in was a crocodile, but it had escaped from a local man’s back yard,” writes Gizmodo’s Esther Inglis-Arkell. “The wild crocodiles choking the rivers were, it turned out, snakes and lizards mixed with the imagination of children.”

It’s kind of thrilling, after all, to think of a huge beast prowling just a few feet beneath the sidewalk you walk on, or floating just under the surface of a city waterway. There is an entire website dedicated to the mythology of sewer alligators (whose founder, unfortunately, declined an interview).

“There’s a curious relationship between urban legend and truth: an implication at the time of the telling that a legend in some way reflects fact, however extraordinary the elements of the legend may be,” writes the folklorist Bonnie Taylor-Blake. The fact is that we do share even the most artificial of habitats with all kinds of feral animals, but they are not exotic. They’ve been here all along.

I first saw the snake years before the police hunt — on Instagram — and I couldn’t believe it. My friend Pat had snapped a photo of it, massive and oily-black, dangling from a tree as he’d been walking his dog on one of Frick Park’s trails. It took a moment, especially on a small screen, to distinguish the snake from the winter-bare branch it rested on, being about the same color.

Pat and I were both born and raised in the neighborhood of Point Breeze, had spent our childhoods playing under the forest canopy of that park and our adolescences drinking under it, and the idea that we could have shared that seemingly safe space with a real live snake longer than my entire body and as thick as my thigh was beyond my ability to comprehend.

Frick Park is a wild-feeling place. It is not a Central or a Millennium or a Golden Gate. It is a forest in the middle of the city, bordered by old steel baron mansions and quiet residential streets. It is full of the type of wildlife you’d see in a Hudson School painting, chipmunks and groundhogs and deer and hawks, with the occasional black or brown bear lumbering through. This snake looked as if it had escaped from the set of Anaconda, like an Amazonian predator lost in Appalachia.

I had to see it for myself. That snake became my personal Moby Dick. I found more evidence on Instagram: a photo a mountain biker had taken when an identical-looking snake slithered into the dirt path in front of him. I wandered the park searching for it, and I brought in old friends, boyfriends, and my parents to help me on my quest. In four years, I never succeeded, and didn’t hear of the snake from anyone else until I saw it on the local news earlier this year.

But snakes are, by nature, elusive and good at going about their ways undetected by humans. David Steen, an ecologist and leader of the Fish and Wildlife Research Institute in Florida, has built a substantial Twitter following by responding to thousands of people’s requests for snake identification and other information about them. One of the most common questions he gets, which is addressed in his book Secrets of Snakes, is “Why is this a bad year for snakes?”

“In general, when people ask this, they are seeing a lot of snakes,” he told me over the phone. “For me, a bad year is a year in which I see few.” But increased sightings of snakes doesn’t mean that there are more in the area than there were before. It could simply mean that people are more aware of their presence, so they’re looking for them and reporting sightings.

People are generally frightened of snakes, and that fear often leads us to hurt them — to the point that we will veer off the road to hit them with our cars if we see them coiled up by the asphalt, as shown in experiments with rubber serpentine decoys. That fear ties back to a mythology, perpetuated through generations, that snakes carry some ill will, a desire to attack humans.

“I like to remind people that snakes are just little animals,” says Steen. “They have nothing to gain from starting a fight with you. They just want to go about their business. And I hope people can appreciate that even in these relatively urban areas, you have wildlife right alongside you, and I think that’s pretty special.”

Beyond open attacks, one of the greater threats that humans pose to snakes is through habitat loss. A new development, with its brush-clearing and construction, will push any snakes that live on that land away to more wooded areas nearby. (And should they end up on a road in their search for the shelter of some trees and bushes, god help them.) But often those more overgrown, sheltered areas are home to humans and their unfounded fears.

A big, healthy ratsnake, like the one spotted in Frick Park, is a sign of a thriving ecosystem — a term that has certainly not always applied to the historically polluted Pittsburgh. It means that trees are flourishing and mice and chipmunks and rabbits are making their homes in their hollows.

It is not a mutant or a monster. It has no ill will toward you or me. It is just trying to make a home where it won’t be bothered. This region has been so inhospitable to so many different kinds of life for so long that we don’t even recognize our own neighbors — we think they are invaders, come to wreak havoc on our civilized homes.

I hope the snake shows himself to me someday, when I’m walking under the trees in Frick Park, but I will understand if he doesn’t. He has every reason to fear me.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How reptiles in the city went from native species to urban legend on Aug 24, 2021.